(Traducción en español al final *kissy face* ❤️)

If you walk around Mexico City it is most likely you’ll run into more than one print pasted over the walls, my friends and I have even found many made by the same artist more than once. Sometimes — jokingly — we even search for the ones we already “know”.

Public space intervention is an old tradition, as ancient as society itself. When looking deeper into printmaking art in Mexico I found some interesting roots.

“When political powers shift, monuments honoring previous regimes are often reevaluated, moved, or destroyed.” — Dunn, McPhee, Rudnick (Art, Protest and Public Space, 2021)

Due to the fact the printing press arrived in New Spain nearly a century after Gutenberg established the basics of printing in Europe by 1440, America developed printmaking art at a different historical period.

At the very beginning — we are talking mid-15th century — when the printing press was out for its commercial use, it produced thousands of indulgences for the Church, among which is The Bible. However when the politicians, scientists, philosophers, and the folk got a hold of the machine the uprising took off, a colossal moment in information history and learning.

Although, it was not until the 18th century that illustrations came on the scene dressed in protest garments:

An early American example is Paul Revere’s iconic The Boston Massacre (1770), which pits colonial Bostonians against British redcoats five years before the outbreak of the American Revolution.

The success of prints as a protest tool lies in their visual messages and range capability compared to manifestos and other academic enlightenment papers, prints are a way to educate the semi-literate and illiterate population, allowing access to express opposition and awareness.

To put into perspective the impact of prints in Mexico, according to the Instituto Nacional para la Educación de los Adultos (INEA), 1900s Mexico held seven and a half million illiterate people, and by the end of the 19th century they represented 80% of the population; fortunately today that number has decreased to just 7.6%.

Las Calacas

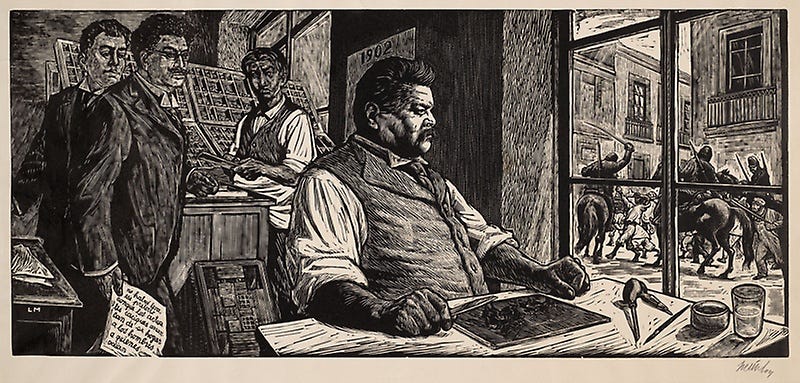

Jose Guadalupe Posada was one of the first and most influential printmakers, some Mexicans recognize his name for his most famous character La Catrina; he was not just the pioneer of introducing humor to modern plastic art, but also the founder of the Mexican Pictorial Movement. Posada made about 20,000 prints that addressed topics concerning religion, natural disasters, and the political agenda. I daresay he was one of the first to document the beginning of the Mexican Revolution (1910-1917).

The Three Greats and, and?!

When we hear the words “Mexican muralism” three male names pop into our heads: Diego Rivera (1886-1957), José Clemente Orozco (1883–1949), and David Alfaro Siqueiros (1896–1974); each of them known for their society depiction: idealistic, futuristic and humanitarian, respectively. Their artwork was impactful indeed, but their diversions took a broader role in Mexican history, The Three Greats were involved in several scandals, organizations, and revolutionary alliances.

*Special mention to some women muralists from the 30s and 40s you probably haven’t heard of: Rina Lazo (1923-2019), worked as Diego Rivera’s assistant and collaborated on the mural “Sueño de una tarde dominical en la Alameda Central”; Elena Huerta (1908-1997); Marion and Grace Greenwood, arrived to Mexico in 1920 and had a close relationship with Pablo O’Higgins.

The Rise and Fall of the Revolutionary Artists

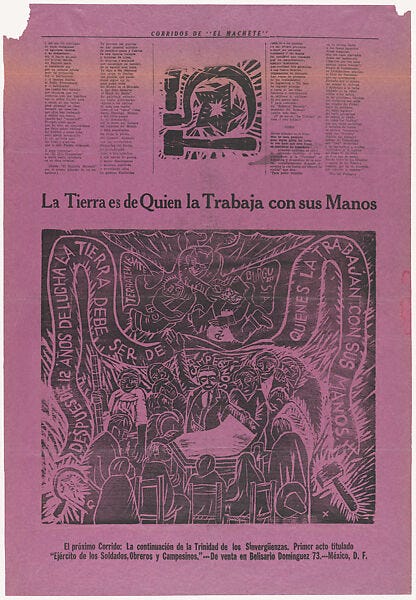

El Machete was a leftist newspaper produced by the Union of Painters, Sculptors, and Technical Workers initiated by Xavier Guerrero, Fermín Revueltas, Diego Rivera and David Alfaro Siqueiros. Their supporters were encouraged to paste newspaper pictures on the walls.

The League of Writers and Revolutionary Artists (LEAR) was an intellectual, communist, leftist, and Cardenist supporter space that questioned and rethought the Mexican art proposal, examined aesthetics, and — most importantly — focused their art efforts on conceiving a utopic society visual; the purpose of the league was to produce a wider art circulation in order to achieve a greater impact beyond the individualistic and classist pursuits of art. It started as a small group conformed by Leopoldo Méndez, Luis Arenal, Pablo O’Higgins, musician José Pomar, economist Makedonio Garza, ballerina Armen Ohanian, and the mathematician Chargoy. Later on, the LEAR had over 600 members and linked with the Partido Comunista Mexicano, they organized congresses, debates, and workshops for the workers. Their magazine (Frente a Frente, 1934-1938), murals, and flyers manifested their repulse towards imperialism, fascism, and war.

“The LEAR tried to establish a direct relationship with the workers, offering them education, cultural activities, and producing images and objects to spread awareness and collaborate with the labor movement.” — Hernandez del Villar (Revolución, arte público mexicano y la Liga de Escritores y Artistas Revolucionarios, 2022)

The Taller de Gráfica Popular (TGP) appeared in 1937 as an organ of the LEAR, founded by the communist painters Leopoldo Méndez, Luis Arenal, and Pablo O'Higgins, they abandoned murals to develop printing technics and promote political change; in the process they also recaptured Posadas tradition. Alas, Siqueiros, Pujol, and Arenal's attempt to assassinate Trotsky in May 1940 provoked a major rupture inside the TGP.

Since then it hasn’t been any other politically committed group that we know of… yet. Today’s printmaking task holds the same value it did years ago, I find hopeful that even when online activism takes place, street imagery and direct intervention will forever have power, at the end of the day printmaking art is a nuclear fraction of protest culture.

Anyway, have you seen any? Tell me about ‘em

Traducción

Si caminas por las calles de la Ciudad de México es muy probable que te encuentres con más de un print pegado en las paredes, mis amigos y yo hemos tropezado con varios hechos por el mismo artista en más de una ocasión. De vez en cuando — tonteando — buscamos los que ya “conocemos”.

La intervención del espacio público es una tradición tan antigua como la sociedad misma. Indagando más a fondo acerca del arte de grabado y el printmaking encontré sus raíces enredadas en peculiares eventos históricos.

“Cuando el poder político se desplaza, los monumentos que honoraban los regímenes previos a menudo serán reevaluados, trasladados o destruidos” — Dunn, McPhee, Rudnick (Art, Protest and Public Space, 2021)

Dado que la imprenta llegó a la Nueva España casi un siglo después de que Gutenberg estableciera los principios básicos de impresión en Europa por 1440, América desarrollo el arte grabado en un periodo dispar al resto del mundo.

Apenas en sus inicios, — estamos hablando de mediados del siglo XV— cuando la imprenta se dispuso para el uso comercial, produjo miles de complacencias para la Iglesia, entre las que estaban La Biblia. Sin embargo, cuando los políticos, científicos, filósofos y la población se apoderaron de la máquina, la sublevación tomó partida; un hito colosal en la historia de la información y el aprendizaje.

Fue hasta el siglo XVIII que las ilustraciones aparecieron en escena trajeadas en prendas de protesta:

Un icónico ejemplo anticipado es La Masacre de Boston (1770) de Paul Revere, coloca una escena de enfrentamiento entre los Bostonianos coloniales contra los Redcoats cinco años antes del estallido de la Revolución Estadounidense.

El éxito del arte grabado y los prints como herramientas de protesta radica en sus imágenes visuales y capacidad de alcance, que, a comparación de los maniefestos y otros textos de ilustración académica, estos — los prints — representan una alternativa para educar a la población semianalfabeta y analfabeta, otorgando así un acceso para la expresión de oposición y conciencia.

Para poner en perspectiva el impacto de los prints en México, de acuerdo con el Instituto Nacional para la Educación de los Adultos (INEA), el México de los años 1900s albergaba siete y medio millones de personas analfabetas, y para finales del siglo XIX representaban el 80% de la población; afortunadamente hoy esa cifra ha disminuido hasta el 7.6%.

Las Calacas

José Guadalupe Posada fue uno de los primeros y más influyentes artistas del arte grabado, algunos mexicanos reconocerán su nombre por su más famoso personaje: La Catrina. No solo fue el pionero de introducir el humor en el arte plástico, sino que también fundó el Movimiento Pictórico Mexicano. Posada elaboró alrededor de 20,000 grabados que abordaban tópicos que van desde la religión, desastres naturales y la agenda política. Me atrevo a decir, fue uno de los primeros en documentar el inicio de la Revolución Mexicana (1910-1917).

Los Tres Grandes y, ¡¿y?!

Cuando escuchamos las palabras “Muralismo Mexicano” tres nombres aparecen en nuestra cabeza casi de manera automática: Diego Rivera (1886-1957), José Clemente Orozco (1883–1949), y David Alfaro Siqueiros (1896–1974); cada uno conocido por su retrato de la sociedad: idealista, futurista y humanitaria, respectivamente. Es innegable que su obra correspondió con un impacto masivo, mas sin en cambio sus enfoques artísticos no los limitaron para verse envueltos en diversos escándalos, organizaciones y alianzas revolucionarias.

*Una Mención Especial a algunas muralistas de los años 30s y 40s de las que puede no hayas escuchado: Rina Lazo (1923-2019), trabajo como asistente de Diego Rivera y colaboraron en el mural “Sueño de una tarde dominical en la Alameda Central”; Elena Huerta (1908-1997); Marion y Grace Greenwood, llegaron a México en 1920 y mantenían una relación cercana con Pablo O’Higgins.

El Ascenso y la Caída de los Artistas Revolucionarios

El Machete fue un periódico de izquierda producido por el Sindicato de Obreros Técnicos, Pintores y Escultores; fundado por Xavier Guerrero, Fermín Revueltas, Diego Rivera y David Alfaro Siqueiros, sus seguidores eran motivados para recortar y pegar en las paredes las ilustraciones de los periódicos.

La Liga de Escritores y Artistas Revolucionarios (LEAR) fue un espacio intelectual, comunista y militante del cardenismo que cuestionó y repensó la propuesta del arte mexicano, examinó la estética y —aún más importante— enfocó sus esfuerzos artísticos a la creación de un visual utópico de la sociedad; el propósito de la liga fue producir una amplia circulación en fin de alcanzar un mayor impacto en las masas lejos de los estímulos individualistas y clasistas del arte. Empezó como un pequeño grupo conformado por Leopoldo Méndez, Luis Arenal, Pablo O’Higgins, el musico José Pomar, el economista Makedonio Garza, la bailarina Armen Ohanian, y el matemático Chargoy. Pronto, la LEAR recogió hasta 600 miembros y se alianzó con el Partido Comunista Mexicano; organizaban congresos, debates, mesas redondas y talleres para los trabajadores. Su revista (Frente a Frente, 1934-1938), murales y panfletos manifestaban el repulso hacia el imperialismo, el fascismo y la guerra.

“La LEAR buscó establecer una relación directa con los obreros, por medio de una oferta educativa, actividades culturales y la producción de imágenes y objetos que no solo eran pensados para concientizar por medio del arte, sino que en ocasiones también eran elaborados para colaborar con el movimiento obrero.” — Hernandez del Villar (Revolución, arte público mexicano y la Liga de Escritores y Artistas Revolucionarios, 2022)

El Taller de Gráfica Popular (TGP) apareció en 1937 como un órgano de la LEAR, fundado por los pintores comunistas Leopoldo Méndez, Luis Arenal, y Pablo O’Higgins; abandonaron el muralismo para desarrollar técnicas de impresión y promover el cambio político, en el proceso retomaron mucho de la tradición de Posada. Lamentablemente, el intento de asesinato a Trotsky en manos de Siqueiros, Pujol y Arenal en mayo de 1940, provoco una ruptura irreparable en el TGP.

Desde entonces no ha habido otro grupo políticamente comprometido del que sepamos… aun. La tarea de el arte grabado y printmaking sostiene el mismo valor que lo hacía hace décadas, encuentro esperanzador que incluso cuando se lleva a cabo el activismo en línea, las imágenes callejeras e intervención directa por siempre tendrán poder, al final del día el arte del print supone un fragmento nuclear en la cultura de protesta.